Parshat Ki Tisa

by Rabbi Avi Billet

Through much of the story of the Golden Calf, the focus is often Aharon. What was he thinking? What was his plan? How could he do what he did? Was he ever blamed for his role? Was he justified or vindicated in the end?

While that is certainly an important discussion, those questions have been addressed in this column in the past. (Linked above and below) However, the same questions can also be applied to Moshe.

Think about it. He was on the mountain, oblivious of any tumult down below. He is informed by God, at a peak in his “chavrusa” (personal study session) with God, “Go down, for the people whom you brought out of Egypt have become corrupt.”

Moshe chooses to listen to everything God has to say before deciding if he’s actually going to go down to watch his people face the music. However, he also makes the choice to stay and talk to God about His plan to destroy the nation, creating a new nation of the Children of Moses. He talks to God, seems to convince God to change His mind, but also even His Middot (character traits, how He operates), to the point that God no longer intends to destroy the people.

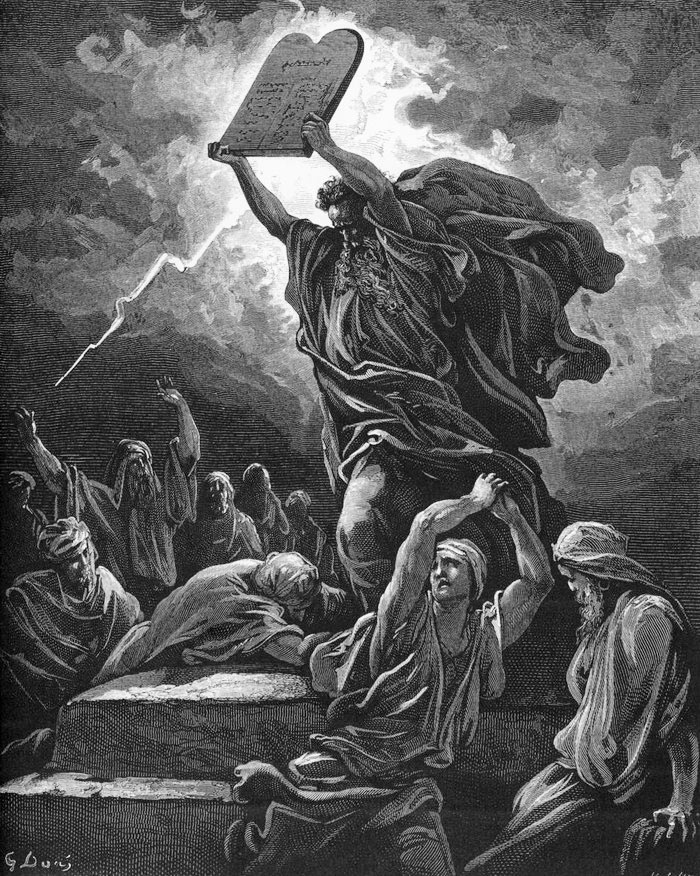

And then Moshe emerges, and in his own anger, he destroys the Luchot (tablets) and orders the killing of the worst offenders, which end up being around 3000 people. Leaving everything else aside, there is a certain irony in that the same man who petitioned that God spare and not destroy the nation is the one who presided over the deaths of half of a percent of the male population.

What led Moshe to think that he could stay and converse with God, after God told him to “Go down” in 32:7?

A very simple reading shows us that God spoke to Moshe in 32:7 using the verb “Vay’daber” (and He spoke) and continued speaking to him in 32:9 using the word “Va’yomer” (and He said). Since there was no interruption from Moshe in between these two introductory verbs, it stands to reason God had a change in attitude between 32:8, the conclusion of the “Vay’daber” portion, and 32:9, when we are told “va’yomer.”

This subtlety is similarly apparent in Shmot 6:2 when we see "Vay’daber" and "Va’yomer" both making an appearance, and the teaching that the former verb indicates God speaking harshly while the latter verb impresses us with God’s mercy is raised by several commentators. In other words, when God said, “Go down, for the people whom you brought out of Egypt have become corrupt. They have turned away from the way I have commanded them by making a golden mask,” God was really angry. But, when He saw that Moshe did not leave right away, and that Moshe was considering how to play his own hand, God saw a leader trying to figure out the best way to save his people. And so He switched gears, speaking to Moshe with “Vayomer,” indicating a compassionate attitude.

God says, “I have observed the people, and they are an unbending group. Now do not try to stop Me when I unleash my wrath against them to destroy them. I will then make you into a great nation.” (32:9-10)

I think what is going on here is quite clear. When God says, using language of compassion, “Do not try to stop Me,” what He is really saying is, “Now is your opportunity to stop Me. Give it your best shot.” And of course, Moshe comes up with a 3-part argument that removes the immediate danger to the nation: a. they are actually Your people whom You took out of Egypt, b. why should Egypt be given fuel to desecrate Your name with a claim that this was Your plan all along, to annihilate Israel in the wilderness?, and c. what ever happened to Your promise to the forefathers?

Let us be clear – the people were guilty of desecrating God’s name in the most egregious of ways. A punishment was in order. But in this particular case, the punishment through the hands of man was going to be far less encompassing and devastating than that which God might have otherwise wrought. (Compare the irony to David's decision in Samuel II 24:14)

Neither Moshe's breaking the tablets or ordering the deaths of thousands seem to weigh against him in the future. In fact the Rabbis taught that God was pleased with the choice Moshe made in smashing the Luchot. He gets overwhelmingly passing grades in this story, despite some of the eyebrow-raising details in his not listening to God, on the one hand, and in his wrath which unfolds against the people, on the other hand.

In terms of Aharon's role, he too is vindicated in his legacy. He certainly does not lose his high priest status, and to this day he continues to be revered as a lover of and pursuer of peace. However in Devarim 9:20 – Moshe tells the people that God got angry at Aharon, and Abravanel maintains the view that Aharon lost any rights to enter the land on account of his role in this story.

Perhaps the difference between the two brothers is that each one had a very different leadership role in relating to the people here. Vis-à-vis God, Aharon never lost his focus. As God sees to the heart, Aharon retained his status as high priest forever. But as a leader to the people, he seems to have given in to their whims a little too much.

Moshe, on the other hand, earned his best stripes here. He showed God how good of a shepherd he could be to his people, and he showed the people that sometimes a father has a right to get angry at his children. It is surely a difficult balance, to be a loving and caring shepherd while also being the disciplinarian father who must take a stand and defend everything that is holy.

But every indication in the story, especially at the end when Moshe's face is shining, demonstrates that Moshe did everything right here. His choices, his decisions, and his actions are all vindicated as he is elevated to the highest status a mortal could achieve.

May we be so lucky that our choices and decisions and actions always turn out to be the right ones.